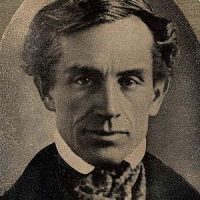

Better known as the inventor of the electric telegraph, Samuel F. B. Morse was also a professor of painting and sculpture at New York University, which was founded in 1832. His appointment that year to the first such professorship in the United States represents a milestone in his mission to promote the fine arts as truly American.

Morse’s reputation alternated between recognition and neglect throughout his artistic career. His training in England from 1811 to 1815 sparked his ambition to create a more nurturing environment for the fine arts in his native country. But the material realities of the American art scene, which lacked institutional support and private patronage, forced Morse to adapt his grandiose plans, and he soon resorted to portraiture as the only marketable genre. After working as an itinerant portraitist in New Hampshire and Vermont, he resided for a while in Charleston, South Carolina, and finally settled in New York City. His clients included not only local dignitaries but also eminent national figures such as President James Monroe.

For Morse, however, portrait painting exemplified America’s materialism. Like Sir Joshua Reynolds, he considered history painting to be the most elevated genre of art. Following in the footsteps of his compatriots Benjamin West and John Trumbull, Morse modernized history painting for an American audience. His House of Representatives (1822-23; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), with its attention to contemporary costume and lack of a single dramatic moment, illustrates this approach. Set in the newly- renovated Hall of Congress, it includes individual portraits of dozens of congressmen, Supreme Court justices, journalists, and janitors, all participating in the orderly process of democratic government. Here, Morse was able to domesticate the grand ideal by fusing it with a more casual tone.

The Gallery of the Louvre (1832-33; Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago), begun the year Morse assumed his teaching post at New York University, best captures his educational agenda. It features an art teacher surrounded by students in the Louvre museum in Paris. In this self-contained ideal world, where students interact with works of art from various old-master traditions, Morse conceived the past in animated relation to the present.

In 1835 he moved into New York Univeristy’s new University Building, constructed in the then-fashionable neo-Gothic style at Washington Square East-on the site of the current Silver Center, the home of the Grey Art Gallery. He took the northwest tower as his studio, as well as six other rooms for himself and his students, who received both theoretical and practical instruction. As an unpaid faculty member, Morse collected fees for instruction directly from his students and was responsible for their welfare. But, greatly disappointed by his failure to secure a commission to paint a mural in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C., Morse soon drew back from the arts and turned his attention to the telegraph and to his groundbreaking research in photography, conducted in collaboration with New York University Professor of Chemistry John Draper. Although he no longer taught after 1841, Morse continued to be listed as Professor of the Literature of the Arts of Design until just before his death in 1872.

Morse never realized his dream of developing a truly American public art, one that educated the populace to new heights of artistic awareness while fostering enthusiasm for a distinctly American heritage. Yet the founding of the National Academy of Design, over which he presided from 1826 to 1842, and his presentation there, first in 1826, then in 1828-29 and 1831-32, of the first educational art lectures in America (published as Lectures on the Affinity of Painting with the Other Fine Arts) were significant steps in the encouragment of the arts in America. And his paintings remain as records of his progressive contribution to the American art scene. His idealistic vision of the role of art education in developing America as a preeminent cultural force is best embodied in the Allegorical Landscape of New York University (1835-36; New-York Historical Society, New York). Here Morse transposes New York University’s University Building from Washington Square to a timeless classical landscape inspired by the work of the seventeenth-century French master Claude Lorrain. Such a struggle to fuse old and new characterizes all of Morse’s involvements in American cultural life.

http://www.nyu.edu/greyart/information/Samuel_F_B__Morse/body_samuel_f_b__morse.html