Nassos Daphnis, born in 1914 in the village of Krokeai near Sparta, arrived in the United States in January 1930. He had been drawing and carving since childhood, and getting beaten for it by the village schoolmaster. In Manhattan he went to work in his uncle’s flower shop, and attended night school to learn English. He worked at his drawings during odd hours until a chance meeting in the New York City flower market with another florist’s assistant, Michael Lekakis, turned his life around. When Lekakis saw some of Daphnis’s drawings, he offered him the use of his studio and a model for a few days each week until Daphnis could find a space for himself.

Eventually, Daphnis bought paints and rented a studio for ten dollars a month. His uncle exclaimed, “Whoever heard of an artist from Krokeai?”

His early paintings, based on memories of Greece, were naive in style and characterized by a strong feeling for color and form. They led to a sale to William Gratwick and to a job crossbreeding tree peonies on the Gratwick estate for many years. Daphnis liked to say that he had two real careers, painting and horticulture. He returned from World War II deeply affected by Europe’s devastation. In a studio he shared with Theodoros Stamos, Daphnis began to paint surreal landscapes, laying on images of ruin with a palette knife.

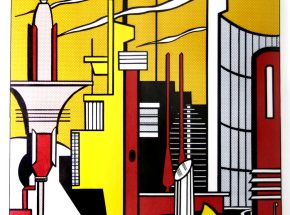

In time, his shapes grew less tortured and more biomorphic-plants and sea creatures-his paint thinner, his colors brighter. And from painting camouflage in the Italian campaign, he “had learned to paint flat”. Now he combined that lesson with the lesson he had learned from his horticultural experience: “nature works in order to create a form in an orderly fashion.”

Those two lessons he combined with a third, learned on a 1950 visit to Greece, where he re-experienced the sunlight rejecting from landscape and from the white houses with such intensity that it appeared to dissolve everything but shape. Geometric shapes in primary colors and black and white took over Daphnis’s work. He sold nothing for years, until in 1958 a powerful new dealer, Leo Castelli, was struck by the simplicity of these paintings and gave him a show the next year from which Daphnis sold several works, including one to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In the mid-1960s, he began to work with spherical shapes; in the mid-1970s he created an environment with a series of modules linked together to form The Continuous Painting (1975), which is 10 feet high and 86 feet long. In the 1980s and 90s, he applied jewellike enamels to canvas to produce the Minoan series, and at about the same time he lightened his palette for another series in which “curvilinear trellises” formed by parallel lines of black, red, blue and yellow appear to shift across a white field.

www.askart.com

Image Courtesy of Marino Gallo

Website

http://nassosdaphnis.com