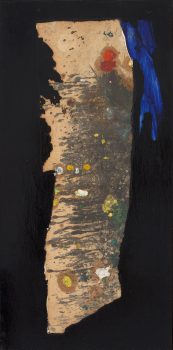

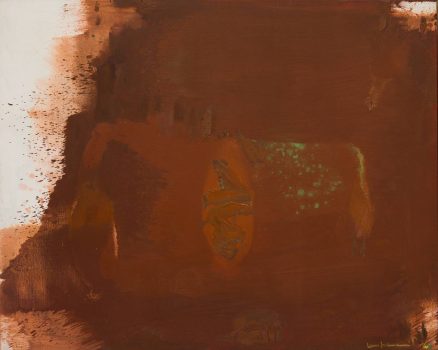

Hans Hofmann’s career as an artist, teacher, and writer bridged the European avant-garde and abstract expressionism in the United States. His later paintings included a radiant palette and loose brushwork. Hofmann always maintained that abstract principles governed his compositions: “Like the picture surface, color has an inherent life of its own. A picture comes into existence on the basis of the interplay of this dual life. In the act of predominance and assimilation, colors love or hate each other, thereby helping to make the creative intention of the artist possible.”

Born in Germany, Hofmann studied in Paris, where he met Pablo Picasso, Robert Delaunay, and Henri Matisse. He later moved to New York, where he continued to teach, instilling in his students a profound awareness of color’s visual dynamics and the freedom they offered him.

Source: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Website

http://www.hanshofmann.org