Georgia O’Keeffe was the second of seven children, and grew up on a farm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. As a child she received art lessons at home, and her abilities were quickly recognized and encouraged by teachers throughout her school years. By the time she graduated from high school in 1905, O’Keeffe had determined to make her way as an artist.

O’Keeffe pursued studies at the Art Institute of Chicago (1905–1906) and at the Art Students League, New York (1907–1908), where she was quick to master the principles of the approach to art-making that then formed the basis of the curriculum—imitative realism. In 1908, she won the League’s William Merritt Chase still-life prize for her oil painting Untitled (Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot). Shortly thereafter, however, O’Keeffe quit making art, saying later that she had known then that she could never achieve distinction working within this tradition.

Her interest in art was rekindled four years later (1912) when she took a summer course for art teachers at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, taught by Alon Bement of Teachers College, Columbia University. Bement introduced O’Keeffe to the then revolutionary ideas of his colleague at Teachers College, artist and art educator Arthur Wesley Dow.

Dow believed that the goal of art was the expression of the artist’s personal ideas and feelings and that such subject matter was best realized through harmonious arrangements of line, color, and notan (the Japanese system of lights and darks). Dow’s ideas offered O’Keeffe an alternative to imitative realism, and she experimented with them for two years, while she was either teaching art in the Amarillo, Texas public schools (1912-14) or working summers in Virginia as Bement’s assistant.

O’Keeffe was in New York again from fall 1914 to June 1915, taking courses at Teachers College. By the fall of 1915, when she was teaching art at Columbia College, Columbia, South Carolina, she decided to put Dow’s theories to the test. In an attempt to discover a personal language through which she could express her own feelings and ideas, she began a series of abstract charcoal drawings that are now recognized as being among the most innovative in all of American art of the period. She mailed some of these drawings to a former Columbia classmate, who showed them to the internationally known photographer and art impresario, Alfred Stieglitz, on January 1, 1916.

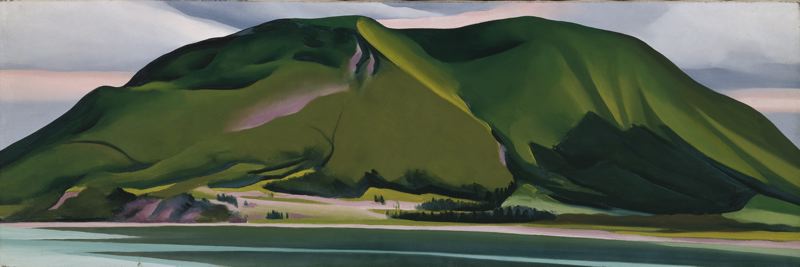

Stieglitz began corresponding with O’Keeffe, who returned to New York that spring to attend classes at Teachers College, and he exhibited 10 of her charcoal abstractions in May at his famous avant-garde gallery, 291, which O’Keeffe knew he would do, but was uncertain of when. A year later, he closed the doors of this important exhibition space with a one-person exhibition of O’Keeffe’s work. In the spring of 1918 he offered O’Keeffe financial support to paint for a year in New York, which she accepted, moving there from Texas, where she had been affiliated with West Texas State Normal College, Canyon, since the fall of 1916. By the time she arrived in New York in June, she and Stieglitz, who were married in 1924, had fallen in love and subsequently lived and worked together in New York (winter and spring) and at the Stieglitz family estate at Lake George, New York (summer and fall) until 1929, when O’Keeffe spent the first of many summers painting in New Mexico.

From 1923 until his death in 1946, Stieglitz worked assiduously and effectively to promote O’Keeffe and her work, organizing annual exhibitions of her art at The Anderson Galleries (1923–1925), The Intimate Gallery (1925–1929), and An American Place (1929–1946). As early as the mid-1920s, when O’Keeffe first began painting New York skyscrapers as well as large-scale depictions of flowers as if seen close up, which are among her best-known pictures, she had become recognized as one of America’s most important and successful artists.

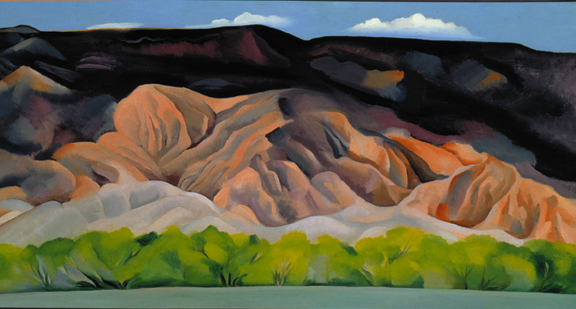

Three years after Stieglitz’s death, O’Keeffe moved from New York to her beloved New Mexico, whose stunning vistas and stark landscape configurations had inspired her work since 1929. Indeed, many of the pictures she painted in New Mexico, especially her landscape paintings of the area, have become as well known as the work she had completed earlier in New York. Indeed, her ability to capture the essence of the natural beauty of northern New Mexico desert, its vast skies, richly colored landscape configurations and unusual architectural forms, has identified the area as “O’Keeffe Country,” Indeed, the area nourished O’Keeffe’s creative efforts from 1929 until 1984, when failing eyesight forced her into retirement. She lived either at her Ghost Ranch house, which she purchased in 1940, or at the house she purchased in Abiquiu in 1945. She made New Mexico her permanent home in 1949, three years after Stieglitz’s death, and continued working in oil until the mid–1970s. She worked in pencil and watercolor until 1982 and produced objects in clay from the mid-1970s until two years before her death.

Website

http://www.okeeffemuseum.org