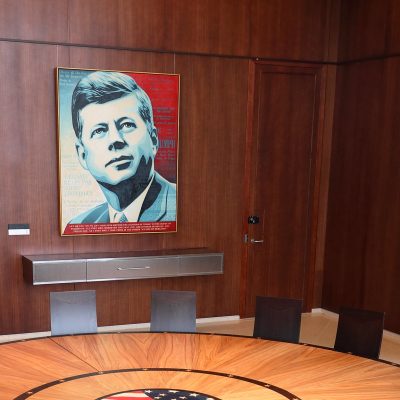

2023 marked the 60th anniversary of Art in Embassies, established by President John F. Kennedy under the auspices of the United States Department of State to create cross-cultural dialogues and foster mutual understanding through the visual arts. President Kennedy understood the vital role of the artist, saying “I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than full recognition of the place of the artist.” This exhibition, which celebrates six decades of U.S. government support of the arts, draws inspiration from Kennedy’s proposition. It is centered on the notion that a successful democracy is contingent upon individual freedom of expression.

In a 1941 address to Congress, which sought to bolster patriotism during a time of war, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt described his vision for a post-World-War-II world as one founded on four universal freedoms: freedom from fear, freedom from want, freedom of speech, and freedom of worship. Inspired by these aspirational community values, American painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell created works for The Saturday Evening Post. The Rockwell images were widely distributed and became iconic representations of American Democracy. However, it was a limited depiction. At the time, the publisher maintained a policy that restricted images to White people only—unless people of color were represented in positions of servitude.

In 2019, artists Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur, in collaboration with Eric Gottesman and Wyatt Gallery, reinterpreted these four freedoms works and brought them forward to represent a more accurate and inclusive depiction of America. Willis Thomas, Gottesman, Gallery, and Michelle Woo had in 2016 established an artists’ collective called For Freedoms, which galvanizes communities and catalyzes change by empowering the voices of artists and creatives. Among its many initiatives, the collective—formed on the principles of community, justice, and love— created the largest public art project in American history, utilizing billboards nationwide to present artists’ distinct voices.

Gee’s Bend (Boykin, Alabama) is a small, isolated Black community in America’s rural South, surrounded on three sides by the Alabama River. Since the 19th century, this remote community has developed a distinct approach to quilting, combining an underlying geometric structure with an improvisational and individualistic style. Like most of her community, America Irby was a field worker. This quilt was constructed from old work clothes and represents the labor and creativity of the quilter and those who toiled in the cotton fields.

Sanford Biggers’s multidisciplinary practice, which integrates film, video, installation, sculpture, drawing, original music, and performance, leans heavily on bringing the past into the present through the integration of found objects and multicultural symbols and tropes. He has described this visual melding as a form of hip-hop or sampling, which, through recontextualization, creates new perspectives and understanding. Pas de Deux, 2016, is part of a series of works incorporating found quilts, which Biggers uses as the starting point for wall sculptures and installations, creating a dance and dialogue between cultures and eras.

Lawrence Weiner was one of the primary figures associated with the emergence in the 1960s of what became known as Conceptual Art. He used language as his primary material and defined art as “the relationship of human beings to objects and objects to objects in relation to human beings.” For Weiner, ideas or concepts could be art, regardless of whether the work had a physical presence. He also welcomed multiple interpretations of his work, even though the words themselves remained the same. Within the context of this exhibition, TO SEE AND BE SEEN, 1972, reminds us that strength lies in a collective understanding of the value of each element that makes up the whole.

Xaviera Simmons is an artist, activist, and organizer. Her diverse body of work includes photography, performance, video, sound, sculpture, and installation and is anchored in investigating history, memory, accountability, and change. In 1998, she began a two-year journey retracing the transatlantic slave trade through the United States, the Caribbean, and Africa. As she traveled, she was moved by both the realities and fictions of history and storytelling, and her subsequent work examines issues related to both the physical creation of the United States at the hands of slaves, as well as the building of the nation’s cultural identity as a White supremacist nation. Simmons’s work creates images and experiences that confront the viewer with essential truths and an urgent call for reconciliation and action.

Pink Family, 2008, is comprised of seven studies of ceramic shards that Araújo saw while on a trip to Mount Vernon, the historic home of America’s first President, George Washington, who was also a Revolutionary War General and plantation owner.

Pink Family relates to the classification of a type of 17th-century Chinese porcelain, much of which was exported from China by Portuguese colonizers who ruled the Chinese island of Macau for over 400 years. (Macau returned to Chinese sovereignty in 1999.)

Paired with quotes from Susan Sontag’s essay, Regarding the Pain of Others, these irrevocably damaged objects are a reminder that handcrafted objects hold the history of their maker and the context of their surroundings. Through image and text, the fragments exist in parallel to the pain of Macau’s colonized community, which was once whole.