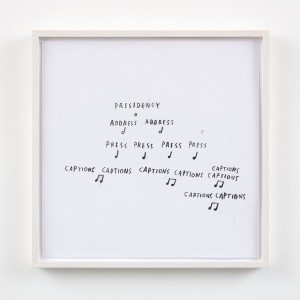

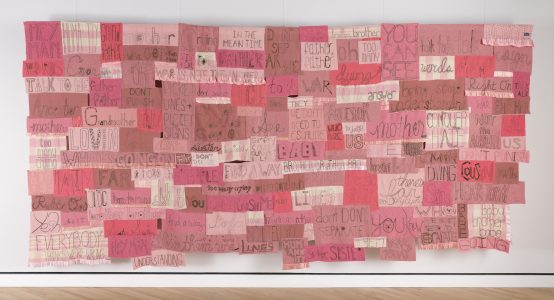

2023 marked the 60th anniversary of Art in Embassies, established by President John F. Kennedy under the auspices of the United States Department of State to create cross-cultural dialogues and foster mutual understanding through the visual arts.

This exhibition, which celebrated six decades of U.S. government support of the arts, draws inspiration from Kennedy’s proposition. It was centered on the notion that a successful democracy is contingent upon individual freedom of expression.