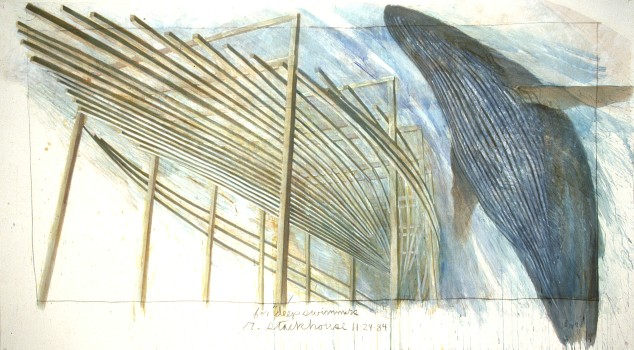

Robert Stackhouse is the artist who builds large wooden A-frame constructions. A relatively small number of people have actually seen a Stackhouse sculpture because they are up for a short time, often on college campuses, and then dismantled. We know this work through photographs — and the artist’s drawings, watercolors and prints.

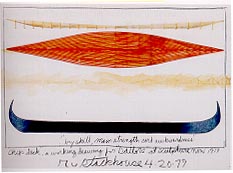

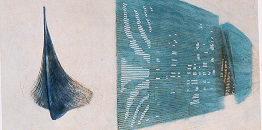

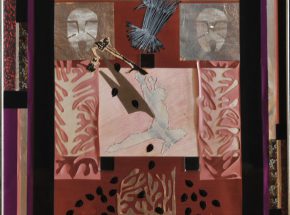

“Drawing is an integral part of my work,” Stackhouse has written. “Source drawings, plans for sculptural projects and documentations of finished installations fill the majority of my studio time. Because I originally studied painting, I conceive of my sculptures two dimensionally rather than in three dimensions. I see them as pictures, not volumetric structures.”

Works on paper dominated “Robert Stackhouse,” a retrospective exhibition of work done since 1969 that was held at the University of Arizona Museum of Art, Tucson, Jan. 28-Mar. 25, 2001. This 51-piece show featured 44 drawings, watercolors and prints; one large sculpture and two smaller ones; two models fabricated by an assistant; and two works that combine two-and three-dimensional elements.

The Belger Family Foundation acquired almost all of this art directly from Stackhouse. The foundation collects a lucky few artists in depth, stores the work at its headquarters in Kansas City, Mo., and welcomes visiting curators and scholars.

Peter Briggs, curator of the University of Arizona Museum, selected the Stackhouse retrospective from among 160 pieces in the Belger collection. The foundation also collects William Christenberry, William Wiley and the graphics of Jasper Johns.

Stackhouse calls his work “a self-portrait” and says that the source of his

imagery is “change as in growth, life and death, journeys, knowledge, and

transformation. “The sources I draw are ships and serpents and shadows,” he adds. “These source images can appear at any time on my project plans or

documentation drawings. My drawing chronicles my method.

Making my sculpture is an experience; drawing is my skill.” The esthetics of drawing and sculpture are “very different,” he adds. “In two dimensions, I’m king of the cosmos and can do anything I please. In three dimensions, I must follow the rules or the piece falls apart.” He calls his work “a kind of dialogue”

between the sculptures and the drawings. Stackhouse never shows his heart in his work. His visual vocabulary and approach to making art have remained

remarkably consistent since his professional career began in 1969.

Stackhouse believes that an artist can work fruitfully with just a few forms. “Whenever I get stuck,” he says, “I draw snakes to get myself started again.” The artist makes drawings that are huge (up to 12 feet tall), poster-like and theatrical, with the imagery centered in a frame and dramatically lit. He draws the frame in pencil and writes the title of the drawing and his name in big letters across the bottom. “Theater had a huge impact on me at an early age,” he explains. “I was a stage hand type in college. I designed and built sets, acquiring skills I would later use to fabricate sculpture.”

Expressive and functional Stackhouse drawings can be termed expressive and functional. Those we call expressive advance his art. He makes them primarily for himself, often in uncommercial sizes, and he can be ambivalent about selling them. Functional works — smaller drawings, watercolors and prints — he sells to make his living. Also included in this category are documentary drawings and work-related notebooks.

In 32 years, Robert Stackhouse has produced so much important work that a modest retrospective selection filled a museum to the bursting point. At a time in his career when he has earned the right to relax, this artist continues to challenge himself. He wants to start painting again, something he has not done since art school. “What really attracts me,” he says, “is an unanswered question.”

VICTOR M. CASSIDY writes on art from Chicago.