Winston Link was born in Brooklyn, New York. He was the second of three children. His father was a public school teacher and exerted a strong influence on his children, escorting them around New York City to see the sights, from battleships at harbor to airplanes in the sky. The elder Link taught his son the use and care of tools and introduced him to photography. Winston developed a lifelong love of tools, becoming a skilled woodworker and a meticulous craftsman. As a teenager, he built his own photographic enlarger and went to work for a local photo store.

Link attended Manual Arts High School in Brooklyn and later the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. He played hockey and was a very popular student, serving as class president all four years in college while majoring in civil engineering. He worked as photographer and photo editor of the school newspaper and, upon graduation, was offered a job as a photographer by a public relations firm, Carl Byoir Associates, in New York City. He worked for Byoir from 1937 to 1942. He never did pursue a career in engineering.

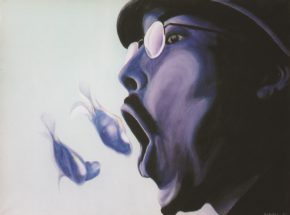

With the onset of World War II, Winston left Byoir and went to work for Columbia Institute Laboratory in Mineola, Long Island, where he performed secret war research for the United States Government. The Long Island Railroad operated tracks right behind the lab. Link had always been fascinated by steam locomotives, and the proximity of the LIRR rekindled his interest, and he started taking pictures. He recognized there was one great problem in shooting photos of locomotives — lighting. He once said, “You can’t move the sun, and you can’t move the tracks, so you have to do something else to better light the engines.” He went on to custom build his own flash equipment required for his large scale railroad photos which he preferred to shoot at night.

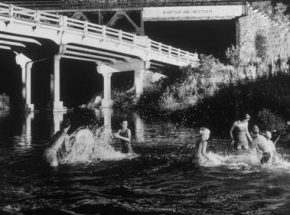

After the war, he was invited back to work at Byoir but declined, deciding instead to become an independent, professional photographer. He soon became known for his skillful photos of complicated factory and industrial interiors. In 1955, Link traveled to Staunton, Virginia, to do an industrial shoot. He knew that the Norfolk & Western Railway passed in nearby Waynesboro and that it was the last large steam-powered American railroad. Link went to observe it. Granted permission to access the tracks by R. H. Smith, president of the N & W Railroad, Link returned the night of January 21, 1955 with his equipment and began photographing the trains.

In the next five years, Winston Link made twenty trips to N & W’s tracks in Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina, producing 2,400 images. Most of the images were produced on 4 x 5 film with a Graphic View Camera.

The last of the N & W’s steam locomotives was taken out of service in May 1960, and Winston returned to New York, where he continued his work as a commercial photographer. He documented construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in New York harbor, photographed for Volkswagen of America as well as a number of advertising agencies.

Link, as much historian as artist, employed his technical skill as a means to document his subjects rather than as a means to fame or fortune. Indeed, he discovered shortly after starting his visual documentation of the railroad that no one was interested in photos of an old technology. However, Winston had also recorded the sounds of the steam engines and found that his high quality sound recordings were quickly gaining recognition. He released the first of six recordings, “Sounds of Steam Railroading,” in 1957, years before his N & W photographs began to garner attention. It was only in 1983 that his photography began to receive recognition as works of art. That same year, Link closed his New York City studio and moved to rural South Salem, New York.

Steam, Steel & Stars, published in 1987, represented Winston Link’s first collection of his railroad photos in book form and dramatically increased recognition of his work. The Last Steam Railroad in America, published in 1995 sealed his status as America’s premier photographer of steam railroading. Exhibitions of his work have been seen throughout the United States, Great Britain, Europe and Japan.

In 2000, Winston Link agreed to creation of the O. Winston Link Museum to be located in the historic Norfolk & Western Passenger Station, in Roanoke, Virginia. The station was restored and refurbished by famed industrial designer, Raymond Loewy, and the museum opened in 2004, with Mr. Link actively involved the planning.

© 2007 O. Winston Link Museum

Website

http://www.linkmuseum.org