Noman Mercer, reared in Manhattan’s pre-Internet, pre-TV days, grew into manhood nurturing a yen for artistic creativity. He studied at Parsons School of Design, but, determined to make his mark in the world of finance, he parlayed his entrepreneurial skills into a multifaceted career as a product designer and an international businessman, including, among other enterprises, the importing of “silverware” gussied up with a then-new feature: plastic handles.

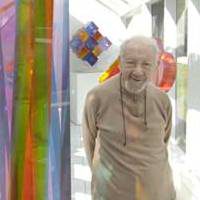

“Maybe that’s why I turned to Lucite to express my artistic ideas when I retired 30 years ago,” he says from the glass-walled sculpture gallery. Mercer’s involvement in creating Lucite sculptures escalated into a new career. After he retired 30 years ago from the company he founded, Import Associates Art, Ltd., he added the 1,400-square-foot workshop where he and his assistant, Jim Ashley, produce each sculpture, working almost every day with a raft of professional-grade equipment: milling machines, polishers, lathes, jointers, kilns – 16 machines in all. Each artwork takes from one to three months to produce.

Odorless and completely transparent, Lucite, he explains, is the least toxic of all plastics, even used for dental implants and many household items. It starts with a mix of chemicals that turns into a liquid that accepts dyes; it can be cast in molds to fit almost any design concept. But Mercer has taken the process to a higher level. He mixes the components for the liquid himself and then adds specially formulated dyes with UV inhibitors that make them impervious to light, even bright sunlight. He says he collaborated on developing the improved formulation with chemists at Rohm and Haas, a Philadelphia company that produces plastic products.

Lucite is not a common medium for artists. There is only a handful of other sculptors, says Mercer, adding that he’s trained several at seminars he has conducted over the years.

http://topacrylicdesigners.blogspot.com; by Jan Tyler | Special to Newsday

September 6, 2007; excerpt accessed April 27, 2011

Image courtesy of Ken Spencer/Newsday