Lubna Agha is one of the leading artists from Pakistan who for the last three decades has taken residence in the United States. Her travels in Muslim lands have opened her eyes to the common heritage Muslim countries share. While each is unique in its own right, she recognizes the commonalities of architectural forms, patterns and cultural objects, allowing her to reclaim overlooked objects of Islamic culture and give them a new life in her art. The yearning she feels for deeper spirituality in her life is particularly embraced in her work.

She noticed that pillars at mosques in Morocco were different from those in her Moghul Lahore and from the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. This is true of other structural elements as well as common objects. She realizes how much is taken for granted or simply overlooked in one’s culture. A desire to inspire a fresh vision of Islamic _cultural heritage has become Lubna’s challenge.

In her words, “My inspiration stems from visual images that once were seen daily but are now part of history. In my paintings, the forms and elements I draw upon become seeds for stimulation. The aim is not to capture those images faithfully, but use them as triggers to take me on paths all my own. My work is about discourse with history, about issues of identity and culture.

“All these have been my points of reference.”

By Marcella Sirhandi

Professor, Oklahoma State University,

Bartlett Center for the Arts

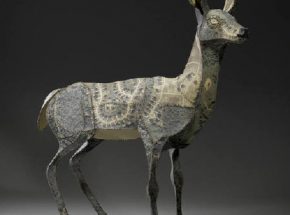

Her vision has less to do with iconography and design than with process and craftsmanship. Images that she chooses to create are diverse, though all had a ready connection to Islamic art or culture. She paints a mosque pillar, a window within a window, a ceiling support for a chandelier, a pen box and rehel (Qur’an holder). The unifying element is the mark-a dot or brush stroke-no lines. The mark is repeated over and over.

The surface is covered with dots and tiny dashes and curls, not unlike the pointillist paintings of Georges Seurat or the frenzied surfaces of Vincent Van Gogh. Lubna’s density of dots and marks, though visually similar to those of the post-impressionists are philosophically very different. Repetition is a conscious physical act that emulates the repetitive actions of craftsmen producing a ware. The rhythmic beats of the hammer of an ironsmith, the chisel marks of the stonemason, or the sawing and sanding movements of the carpenter are relived with each dot and brush stroke.

The patterns her pieces flaunt embody the geometry and abstraction inherent in traditional Muslim architecture. Thousands of dots form designs that might have come from Moghul mosaics, patterned brick walkways, diapered domed ceilings, jalis (intricately carved screens) or carved wooden staircases. It should be noted, however, that Lubna is not trying to relive an historic tradition.

Dr. Shundana Yousaf of the Pratt Institute of New York emphasizes that “We must not assume a passive translation of a referent or an original preceding her creative act, but be careful to grant her role as an active aesthetic re-creator of these works. Lubna, faithful to her modernist training, is insistent on foregrounding the here and now of her agency. She prefers not to be profiled as an antiquarian who only reluctantly acknowledges her modern conditions of existence, or who mutes her contemporary responses. Instead, she demands recognition as a modernist with modern aesthetic sensibilities, imbued with all modernism’s lately fledged myths while irresistibly drawn to the beautiful residues of an older world she has periodically encountered all her life, first as a youth, later as an accomplished photographer-and always as an artist with an artist’s eye.”

Finding her Islamic roots has become paramount to her as she embraces the artistic heritage of Pakistan and Muslim culture. In the intense color and rich pattern seen on the rehel, she embraces meticulous craftsmanship and design. The joyous colors show her complete involvement in her new work-it is making Islamic art and architecture personal. She has foresworn the speed of the twenty first century, choosing instead time-consuming, labor-intensive devotion to historic practice. Each daub of paint relives for example, the process of a craftsman beating on a piece of metal, both in the physical action and in the historic concept. Each stroke becomes important because it represents the physical act of making.

Writing in the exhibition catalog for Lubna’s exhibition in Canada, curator Nadia Kurd observed the imposing presence of Lubna’s paintings when juxtaposed against architectural renderings: “In these works, not only do these images integrate elements of architecture but also incorporate a brushwork style consisting of points. This method of painting gives her subject matter a distinct brilliance in color and shape. The abstract images in her work challenge some of the immovable qualities of architecture to provide an ephemeral sense of two contradictory senses: infinity and oneness.”

Website

http://www.lubnaagha.com