Elizabeth O’Neill Verner was born in Charleston, South Carolina. Her artistic gifts were encouraged and developed by her maternal grandfather, Henry Franklin Baker, who had been a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, a Charleston artist. After graduating in 1900 from Ursuline College in Columbia, South Carolina, Miss O’Neill enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. She fell under the influence of Thomas Anshutz, and his encouragement caused her to work hard at her technique. After two years she left, and taught for a year in Aiken, South Carolina, before returning to Charleston, where she lived out her life.

In 1907 O’Neill married E. Pettigrew Verner and had two children by him. Art was her avocation. In 1908 she and Leila Waring shared a studio. Verner was a founder of the Charleston Sketch Club. Etching was then popular among amateur art associations, and she learned the techniques of printmaking with Alice Smith. Verner was among the founders of the Charleston Etching Club in 1921. That year the Southern States Art League held its first exhibiton, in Charleston, and she served on its board from 1922 to 1933 and exhibited with it until its demise in 1950. In 1923 one of her etchings won third prize at the Charleston County Fair, a humble beginning for one who was to achieve a national reputation. In 1924 she was represented at the International Exhibition of the Chicago Society of Etchers. Then her husband died unexpectedly, followed shortly by her mother, leaving her without means of support. Alice Smith persuaded her to become a professional artist. She opened a workshop and showroom on Atlantic Street, where Leila Waring, Alice Smith, and Anna Heyward also worked.

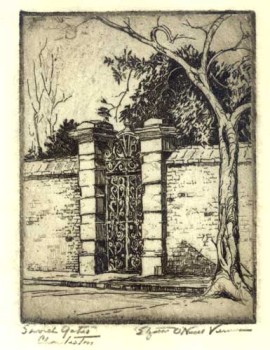

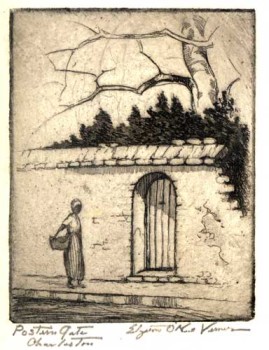

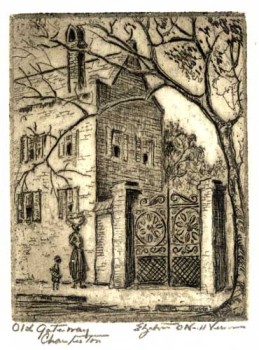

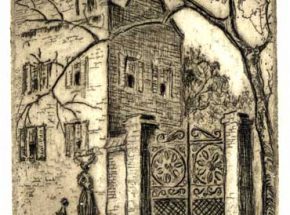

In Mrs. Verner’s words, “Until 1925 I had two hobbies, art and love of Charleston. I combined them into one profession.” From the outset, her favorite subject was the Lowcountry of South Carolina – its marshes, flowers, trees and birds, but above all, Charleston itself – its quaint and charming streets, alleys and church spires, its gardens, lamp posts, gateways and people. Her interest in the architectural environment of Charleston was not limited to art. She was a charter member of the Society for the Preservation of Old Buildings. Her art, more than mere words, conveyed what it was about Charleston that merited preservation.

In 1926 Verner received her first commercial commission – for twelve drawings to illustrate a promotional brochure on Hollywood-by-the-Sea in Florida. That year she bought her own press for printing etchings. Most of her works were sold to tourists as souvenirs of the city. In 1928 she did etchings of Savannah, the preservation of which also interested her. In 1929 Verner was asked by the Mount Vernon Ladies Association to execute drawings of that house for use in fundraising, which was a labor of love for the artist. A trip to Europe included study at the Central School of Fine Arts in London in 1930. A trip to New York City in 1932 resulted in the sale of drawings to Rockefeller Center, and of twelve others for reproduction as postcards. At Doll and Richards Gallery in Boston she exhibited etchings in 1934, including one called Kitchen Courtyard, and in 1935 she showed not only prints, but pastels, which she had just begun doing. After a trip to Japan in 1937, she perfected a technique for applying layers of pastel to silk mounted on wood, which she called vernercolor. Although increasingly interested in pastels, she did not abandon drawing and etching. In 1939 she exhibited twelve etchings of Japan at Boston. Her views of Williamsburg and West Point were reprinted, and in 1950 she was commissioned to depict Princeton University.

Verner’s first book, Prints and Impressions of Charleston appeared in 1939, and in a larger format in 1945. It was called “the best book of Charleston pictures that has been published: by the Christian Science Monitor, the New York Herald Tribune, and the Boston Post. A second book, Mellowed by Time, appeared in 1941, and her drawings were accompanied by her romantic reminiscences of Charleston in bygone days. Forty-three of her non-Charleston etchings appeared in Other Places, her term for the world apart from the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper. In the late 1920s she had illustrated the title page of the Charleston edition of DuBose Heyward’s Porgy, and she also illustrated Peter Michell Wilson’s Southern Exposure, Howard Mumford Jones’ French and American Culture and his The Carolina Low Country, a compendium of spirituals.

In 1947 Verner was awarded honorary degrees by the University of North Carolina and the University of South Carolina. Other honors followed. She had one-man shows in Charleston in 1963, at Manila in the Philippines in 1964, in Spartanburg in 1970, Columbia and Sumter in 1971, and Beaufort in 1972.

A body of her work was bequeathed by George Graves to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1933. Her work is also represented in Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts, the High Museum in Atlanta, the Library of Congress and the Chicago Society of Etchers. Besides the already-mentioned Charleston Sketch Club, Charleston Etching Club and Southern States Art League, she was also a member of the Carolina Art Association, the Art Association of New Orleans, the Chicago Society of Etchers and the Washington Watercolor Club.

Verner considered her contribution to historic preservation to be her greatest achievement. Her efforts resulted in the preservation of many buildings, but the character of the city changed nometheless. Her artworks capture something of what DuBose Heyward called the “faded aroma” of the past. Artists have played an important role in the life of Charleston since the 1700s, but none managed to become so closely identified with that unique city as Elizabeth O’Neill Verner.

The South on Paper: Line, Color and Light, Robert M. Hicklin Jr., Inc., Spartanburg, South Carolina, 1985, pp. 64, 65.

Copyright 1985 Robert M. Hicklin Jr., Inc.

Website

http://www.vernergallery.com